Made up of various seeds and spices, El Salvador’s national spice, relajo, represents just how truly delicious something can be when diversity comes together. With ingredients such as cinnamon sticks, bay leaves, sesame seeds, chiles, and achiote, relajo is a traditional spice mixture used in a variety of Salvadoran cuisines such as pavo (turkey), panes de pollo, and Salvadoran tamales. It is the central ingredient that makes these dishes Salvadoran. Without this, these foods’ main identity would be stripped. Upon looking at the spice, one can see right away that each individual spice and seed that makes up the mix is visible, it’s prevalent and potent. From the fiery-orange red of the achiote to the pop of white from the pumpkin seeds, relajo serves as not only a visual reminder of uniqueness, but a symbolic one as well.

For me, being Salvadoran is the relajo to my personality. It has shaped every part of who I am from my fashion, music, and academic interests. Just like relajo, my Salvadoran identity is comprised of numerous components unique to me –– the same goes for everybody in their own regard. At our core is relajo, and what makes up the relajo will be different, but beautifully distinct to just us. One main component that makes up my relajo, is my own personal relationship with my ethnicity, one that oftentimes, unfortunately, is one of disconnection. When the idea of writing about a personally significant cultural spice came up, I initially blanked. It was embarrassing to not remember how crucial this spice is to El Salvador. Obviously, I knew it existed, but not being able to immediately recognize it precipitated a lot of internal reflection. If I had previous knowledge and personal experience with the spice, why did it take a google search to remember that it even existed? I hated the feeling of realizing that maybe I wasn’t as connected with my Salvadoran identity as I thought. Writing this piece, however, has brought along much more insight and peace regarding this raging internal conflict of mine. Sitting down and really thinking about what this spice represents and means to my culture let me understand that every single intricate part of me is perfectly curated to make up and represent my heritage. That includes a strained cultural relationship that I am trying to heal.

Being Salvadoran is something that will always be a part of me, and there is no amount of gratitude sufficient enough to express how thankful I am for that. What makes it even more riveting is the fact that internal Salvadoran relajo does not just pertain to Salvadorans, but to every culture. With cultural identity you must know it’s there inside of you and you cannot forget that––because if you do, then it is not the same but something completely different––something not you.

زَعْتَر

Spice. They add rich, enormous flavor to your favorite dishes. However, spice offers much more than flavor. They bring comfort, memories, culture, and even power. Throughout history, people have found immense value in spice, to the point where people and cultures were colonized for their rich spices. Spice was much more than flavor; they were like gold, and people would do anything for those bits of powder. An individual spice holds power, but what about when you mix those powerful spices together? Does it create something newer and greater? This is exactly what you get with Za’atar (زَعْتَر). Za’atar is a Middle Eastern spice blend composed of five different spices: oregano, thyme, sumac, sesame seeds, and salt. Za’atar is a staple in any Middle Eastern household; it is commonly eaten with olive oil and pita bread and has a history as a health food. Each spice in the mix has their own history and their own power. By combining them, you get a new spice blend with its own story. Just like how Za’atar is composed of a diverse group of spices, Armour is comprised of a diverse group of creatives who each have their own personalities, stories, and experiences. Individually, everyone offers something unique. When brought together, however, they have the opportunity to create something diverse and great that you wouldn’t otherwise have, which is Armour. Just like how each spice of Za’atar has a story, each member of Armour has a story.

Leena:

Leena is Armour’s current Editor-in-Chief and a junior from Milwaukee, WI studying fashion design and business. When deciding the editorial’s theme for this semester, she reflected on what spice means to her. Amour portrays itself uniquely and is everything but bland, giving Armourites the ability to flex the creative parts of their brain. In her words, spice is all about rejecting the basic, expected, and bland; it’s about making something spicy and flavorful, giving Armourites the opportunity to create anything from campy to serious. As Editor-in-Chief, Leena brings Armourites the opportunity to see their ideas come to fruition by providing the resources and community to make something great.

Bri:

Bri is Armour’s Social Media Director and a sophomore from Moraga, CA studying ancient studies and marketing. She sees spice as a reflection of human beings. Each spice and each person is a vehicle to telling an individual story and representing a culture, and both are more than meets the eye. Bri also sees versatility in spice and people. Spice can take different forms and change character when you grind them down, heat them up, or combine them with other spices—which can be seen as a reflection of human beings and life stories. As an ancient studies major, Bri loves exploring stories and specifically how past stories connect with us today and how we connect to those around us. She brings connection to Armour and loves connecting us on campus, to the St. Louis community, and across the globe.

Max:

Max is a photographer for Armour and a freshman from Tenafly, NJ studying biology and art history. To him, spice brings memories. Different spices are important to different cultures and evoke memories for everyone. Max brings an interdisciplinary mindset to Armour. As a student of both STEM and the arts, Max loves exploring the application of biology to design. He enjoys the analytical side of how we ask questions and tell stories and then fuses that analytical side into something creative.

Leena, Bri, and Max all bring different majors, backgrounds, and experiences yet have similarities in why they joined Armour. They all enjoy the creativity of the magazine and being able to meet new people and create connections at WashU. They have a variety of interests like creative directing, styling, social media, photography, and many more. Regardless of the difference in their interests, they all contribute to the magazine, website, campus presence, and cultural curator that is Armour. Without them and everyone else, we wouldn’t have Armour, just like we wouldn’t have Za’atar without each of the individual spices. Like the different spices of Za’atar, Armourites come from different walks of life, and they all bring their own unique and creative flavor to Armour.

The windshield wipers hit the sides of my window just a beat off of the actual rain falling down. Listening to Amjad Khan, I reach to switch the station as I hear the school bell ring. Now in my car are the sounds of American pop as I see my grandaughters run out of school to meet me at the car. In an instant, I see my son reflected in his daughters as they reach the car. It’s hard to imagine that I’ve been in this country long enough for a school to touch two generations. The labors of my hard work are seen in this simple truth. With Taylor Swift now playing in the background my grandaughters regale me with tales of their days. My youngest granddaughter apparently hates her teacher and the conversation on how her teacher is out to get her takes up the majority of the car ride. She speaks so fast it’s often hard for me to keep up with what she’s saying so instead I smile and nod along. Halfway along the ride, we pass a Starbucks and immediately the story comes to a halt. Less than a second later I am met with two piercing screams begging for Starbucks. “Please, Dadu can we stop?” shout the two little voices. My son already believes that I am to much of a pushover with his children, but as a grandparent what am I supposed to do other than spoil them. However I for some reason decide to listen to him this once “no, we can make chai at home”. “Like a chai tea latte?” I hear a voice squeak from the back seat. I cringe visibly at this question. However proud I am of my success in this new nation I feel a pang everytime I realise the cost that came with it, the disconnect of culture. It wasn’t an immediate thing and it snuck up on me so quickly and quietly I didn’t realise the extent of my assimilation until it was too late. My son’s speak to me in a form of Benglish with hints of their roots peaking in through our conversations while my four grandchildren can’t speak to me in their native tongue at all. My grandchildren call me in grandpa in front of their friends sometimes when they think I’m out of earshot, in an attempt to fully Americanize their experience. I understand the need to do so. Even I changed my name to Sam in order to make it easier for my white coworkers to address me, for them to feel comfortable to speak to me and yet my heart still tugs everytime my grandaughters feel the need to switch their culture to fit in. I thought the era of “white being right” was over. So yes I say no to the starbucks “chai tea latte”, (why they would call it tea-tea is still beyond me). Instead I offer to make them their own drink. We get back to my house, only a short 15 minute drive from their own home. As we enter Simran my youngest sulks after the loss of her Starbucks. I send my oldest grandaughter Anjali to grab the mortar. Simran now eager for her own task after seeing her older sister be assigned a job asks what she can do. I tell her to be patient for now, something I was never able to do when I was her age. I see myself reflected in both of them a fact I am sure to remind them of frequently. In her patiently awaiting eyes I see myself waiting at my mothers side for her to make me chai after school. I only knew life in India from after the partition but as I waited at her side she would tell me tales of Bangladesh and her home. I miss her more than ever now and make the mental note to tell my wife that we need to make a trip to India soon, my mother won’t be around forever. As I grind the spices, Simran now desperate to be part of the process begins to fire off questions of what I’m doing, these usually involve a why after each step that I complete. I ask her to pass me the cardamom. The same task that my own mother used to ask me to do. My mother used to tell me that cardamom had special powers. That it could heal illnesses and cure sadness, so I retell the same truth to my grandaughters. I tell them that Starbucks was so inspired by Indian culture that they wanted to share those powers with the rest of the world. I tell them that their food their culture is something that the world appreciates. The chai is done. I wait for their reactions as they take their first sips. I chuckle in response as their eyes go wide and their smiles even wider and as we sit around the kitchen table Simran asks “Dadu what did you do as a kid?”. And with that I see my mother in myself and the repeating of history within them. Culture can never be lost when stories of life still exist. And so I begin.

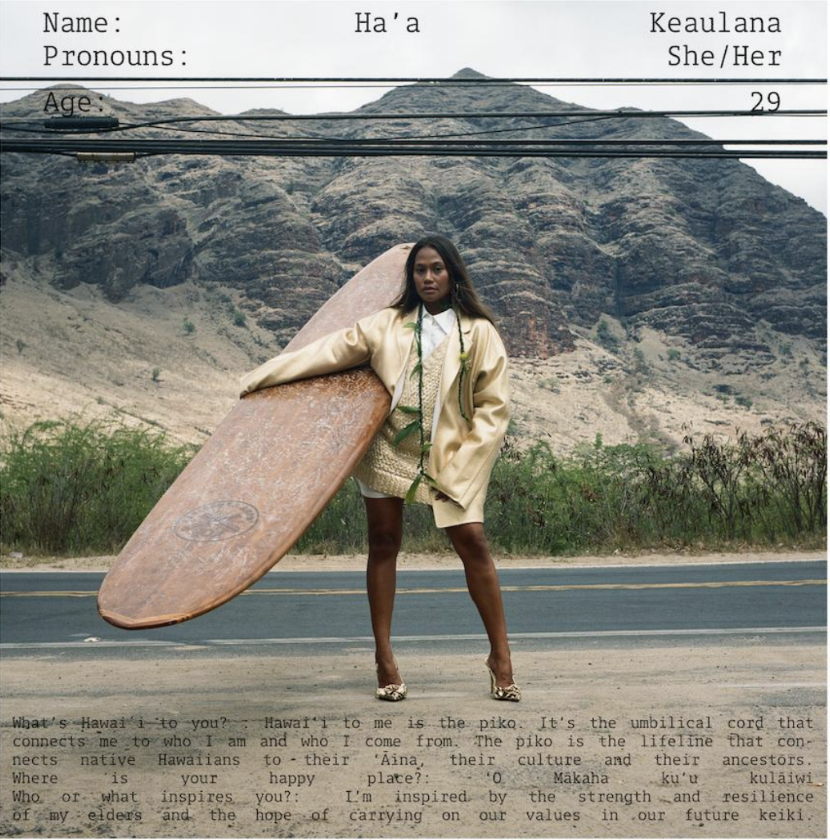

harvested from the mountains and volcanic rock, hawaiian salt cannot be found anywhere else on the

planet. red salt belongs to the ocean and its heartbeat as the waves welcome new souls to the islands of

hawaii. found in dishes like poi, kalua pig, chicken long rice, and haupia after a long day of racing

dirtbikes or the surf, salt is the flavor of home.

the true history of hawaii has always been a bit of an open secret. within a culture that rests beneath the

postcards, social media posts, and illusions of paradise, native hawaiians have fought to secure the

richness of their lands and rights as beings. people of all ages, from elders to keiki (children) have rich,

tanned skin and a blended story to tell. they are hawai’i nei, or the children of hawaii, the sovereign

protectors of the islands. mana (power) flows through their veins as ancestral stories are kept alive

through chanting oli from generation to generation.

before there was salt, there was the ocean. as the islands hardened out of volcanic rock, native hawaiians swore to protect the life of lands as its sacred children. to take care of the land meant nurturing its natural resources, and teaching stories of survival for generations to come. as settlers began to plunder the lands for sugar, salt became a necessity. although the strangers haven’t left, hawaii has been transformed.

what once was only kanaka maoli (native hawaiian) has now become ‘hawaiian’ — an identity for those

born into the lands with descendants of hawaiian ancestry that have intermarried with asian settlers.

hawaiian food became an amalgamation of chinese, japanese, korean, and filipino flavors. to this day, this

has not changed. what has changed, however, is the power of the native hawaiian voice to demand

change. natives have said that we must honor the sacred lands, the oceans, and all divine creation to

protect what hawaii has left. natives have been forced off the island amidst limited access to drinking

water and heightened military and tourism presences. a ‘taste’ of hawaii has become a lethal bite.

entrenched in the jaws of loss, locals are asking the world to change how it consumes the livelihoods of

others.

waikiki beach, centered within the downtown hub of honolulu, is the first stop on any visitor’s journey.

rich with night sailing, surfing, hula dancing, and traditional lei-weaving, culture seemingly flows through

the nightlife as easily as the ocean breeze. one look closer reveals that native hawaiians have been

effectively removed from the ‘aina, or lands, they swore to protect. traditional fishponds have been

flooded to ‘build’ waikiki, with imported sands to strengthen the protection of the popular beach.

skyscrapers tower over ward village, a short walk from the beach, empty sculptures of glass that reflect

the sinking reality: the beautiful island of o’ahu is no longer hawaiian. forced away from beautiful

sunsets, vast oceans, volcanoes, and sacred mountains and limited to either homesteads or living on the

mainland, the culture is at risk of immense loss. what is hawaii if not hawaiian? cultivated with love, loss,

and longing, what have we done? what can we do, before its destruction?

step aside from the tourist-targeted lu’aus, fire dancers, and grass-skirt hula dancers as they perform for

audiences under the moonlight. listen closely to the songs, to the cries of the ancestors, and their

salt-stricken tears. search for the true heartbeat of hawaii, not the artificially curated flavors forced down

our throats. look closer to the messages of the local people and cultural richness to taste the truth.

to taste the salt of the ocean is to taste the same salt that flows in our veins. to taste it is to taste the world itself, all the generations that have come before us that blend into an endless path of convergence.

to taste is to reconcile with one’s heart, land, and love. so, to taste, do so gently.

photo reference(s) to accompany piece:

hawaii youth fashion editorial for numero berlin; shot by luke abbey

https://ajatoscano.com/Hawai-i-Youth

Creative directors Bri Lee, Victoria Briggiler, Lilly Vereen

Photographers Izzy Silver, Owen Rokous

Featured Profiles Yasmin McLamb, Simmy Ghosh, Belal Hammad, Noé Umaña-Ramos

Stylists Yasmin McLamb, Simmy Ghosh, Belal Hammad, Noé Umaña-Ramos

Writers Yasmin McLamb, Simmy Ghosh, Belal Hammad, Noé Umaña-Ramos

Armour Magazine Season 30 — F/S 2024